Shannon Holicza is a rarity.

Her path to the driver’s seat sounds familiar on the surface. Like many others in the trucking industry, she came from a family of truck drivers, learning tricks of the trade while riding along with her dad. By the time she was a teenager, she already knew how to handle most of the paperwork.

A first job at the wheel of a gravel truck evolved into overnight loads, some work in Western Canada’s oil fields, and then long hauls with Bison Transport. Family members like to poke fun at her for that, calling her a “wimp” because they all drive logging trucks. But it’s good-natured ribbing. She just prefers the open highway.

The difference in her story takes the form of a pronoun.

Holicza is a she in an industry dominated by he.

Barely 3.5% of Canada’s 300,000 truck drivers are women, according to labor market data from Trucking HR Canada. Hone into the 181,000 tractor-trailer drivers who work specifically for trucking operations, excluding drivers like those who operate medium-duty trucks or consider themselves part of another sector like construction, and the National Household Survey puts the share closer to 3%.

“Women don’t look at trucks, or supply chain, or warehousing, or even trucking and say, ‘Hey, there’s a place for me there.’”

– Ellen Voie, Women in Trucking

Either number is downright anemic when considering that women account for 47% of Canada’s workforce.

A growing list of industry programs have tried to move the needle, offering training scholarships for female candidates, mentorship programs, even dolls and Girl Scout badges to raise awareness among little girls.

Such programs can be limited to dozens of participants, though. Even Trucking HR Canada’s Women with Drive event – one of the nation’s largest initiatives that focuses on the industry’s women – attracts a few hundred participants at a time, largely from management ranks.

But each initiative still helps to plant some all-important seeds, says Kelly Henderson, executive director of the Trucking Human Resources Sector Council – Atlantic. She offers the example of her organization’s regional Women’s Leadership Program that will help mentor women who ultimately shape fleet policies, procedures, and general thinking around female candidates.

“We are seeing more women being considered or securing positions, higher management positions, than maybe what we did five or 10 years ago.”

Changing the conversation

But there appears to be a need to steer the public conversation around women truck drivers, too.

“Women don’t look at trucks, or supply chain, or warehousing, or even trucking and say, ‘Hey, there’s a place for me there,’” says Ellen Voie, CEO of Women in Trucking. Holicza’s fleet has introduced a “We are Drivers” campaign using tools like social media to help shift perceptions. Stars in that campaign include Amber Balcaen, a racecar driver, and bobsledder Christine de Bruin.

Shelley Uvanile-Hesch just wishes there were more promotional programs like it.

“We don’t focus enough on the women that we already have in existence in our industry,” says the CEO of the Women’s Trucking Federation of Canada. “How do we attract new people in if we don’t show people what we have?”

There are misconceptions to address at the very least. Henderson points to myths that still need to be tackled, such as whether women would need to sacrifice motherhood for a driving career. There are women who had children and a career on the road, she says.

Holicza refers to other barriers that have faded away since she first began driving. Gone are the days when the search for a bathroom meant knocking on the door to ensure there were no men inside before slipping into a stall. Aside from the limited bathroom access that everyone is facing during Covid-19, it’s much easier to find a women’s washroom, she says. Some truck stops even incorporate salons that cater specifically to women.

The discussions about women in trucking have changed in recent years, adds Angela Splinter, CEO of Trucking HR Canada. In early Women with Drive events, for example, panelists focused on the need for accommodations like flexible hours or childcare to attract women. Today it’s more about celebrating the women who have established themselves in leadership roles.

The power of mentorship

Formal mentorship programs that leverage existing female employees are recognized as a powerful tool to retain women within employee ranks, too.

“Women want to be in an industry where they’re able to connect with others,” Splinter says. “We need to show this is an inclusive industry.”

“As human beings, we relate to someone that looks like us and has a similar story,” agrees Tracy Clark, Bison’s director – driver recruitment and retention. It’s just one of the reasons why

the fleet has doubled its number of female in-cab instructors in the last year. All four of them are helping to guide peers – and eliminate an undeniable barrier to over-the-road training.

Imagine if your 26-year-old niece said she secured a new job in the supply chain and had to share sleeping quarters with their boss, Voie explains.

“We send students out with their trainers for weeks at a time and they’re expected to not use the top bunk when the truck is moving. That’s when bad stuff happens.”

It’s just one example of the real and perceived safety barriers to overcome. In one Women in Trucking survey, participants rated their personal safety at 4.4 out of 10. The U.S. Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration (FMCSA) is also in the midst of a multi-year study into crimes against female and minority drivers.

Holicza admits some of her own friends expressed concerns when she first began longhaul work. “I’ve never had any major issues,” she stresses, “but I’m also very street smart.” When choosing places to park overnight, she’s always careful to choose well-lit areas, formal truck stops, and weigh scales.

Male counterparts may not give such things a second thought.

New hires

Meanwhile, training programs across the country are helping to highlight available driving opportunities and cover the tuition at driver training schools. The class counts are relatively small, but several have realized high retention rates, Splinter says, referring to Alberta’s Women Building Futures program as an example.

Clark points to the YWCA’s Changing Gears program, which includes guidance on what its trainees in Western Canada should look for in a carrier.

“It’s not in the hundreds,” Clark says, referring to the reach of such programs. Class sizes are typically closer to a dozen. “These are just the groundbreaking programs.”

Starting young

When it comes to breaking ground, there are other initiatives looking to shape the mindsets of those who are a decade or more away from driving jobs. Think of children’s books, dolls, in-school visits, and Girl Scout patches.

Children begin to take the first steps in career paths as early as Grade 7 and 8, says Uvanile-Hesch. It’s one of the reasons why her group always gives school board representatives and educators free admission to its conferences.

“A lot of companies are only worried about filling the hot seat,” Uvanile-Hesch says. “If you don’t teach kids about an industry, how are they going to know about it?”

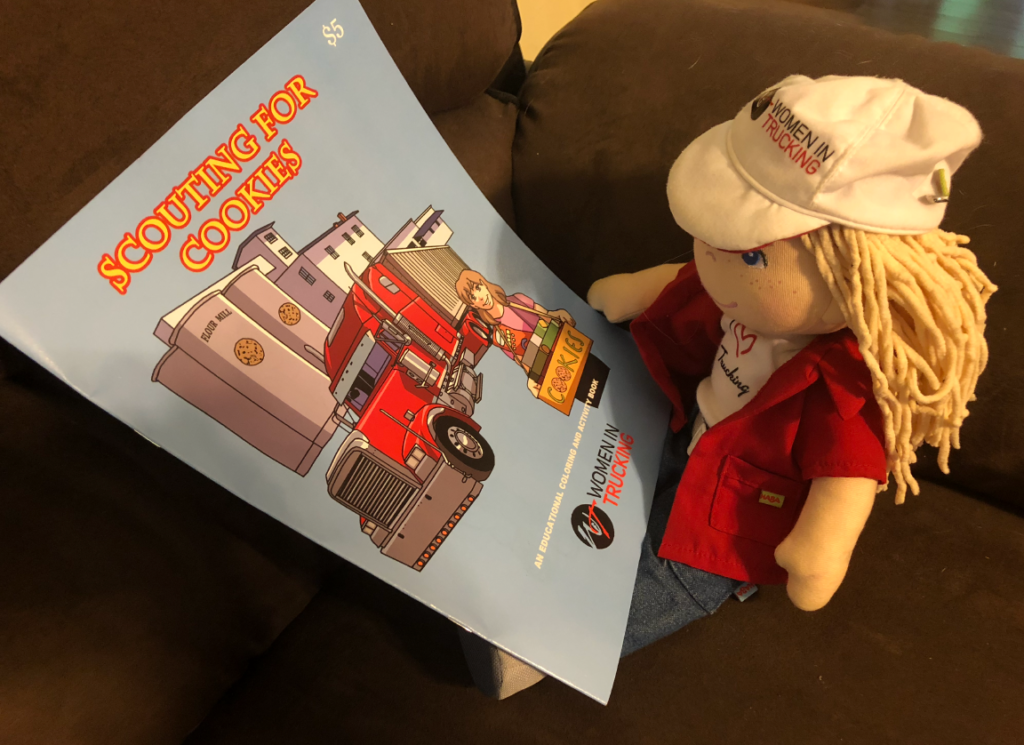

Women in Trucking has transportation patches that can be earned by U.S. Girl Scouts and Canadian Girl Guides. South of the border, Ryder helped to introduce the Girl Scout Cookies and Supply Chain program.

“We want little girls to look at a tractor-trailer on a road and then say, ‘Mommy, that’s my cookies in there,’” Voie says. “We want them to look at trucks on the road and make a personal connection.’”

The personal connections have even extended to include Clare – a 13-inch doll who wears an “I Heart Trucking” T-shirt and a Women in Trucking cap. The packaging shares the story of how she reached the driver’s seat.

Take that, Barbie.

The benefits

Growing the ranks of female drivers may also offer benefits beyond helping to address the trucking industry’s intensifying driver shortage. Male truck drivers are 20% more likely to be involved in a crash, Voie notes, pointing to research by the American Transportation Research Institute.

“Once we start getting the industry to understand that women are safer, better with customers, better with paperwork, women are more loyal, women have less turnover, women feel their pay is fair,” Voie says, “the person I’m describing is someone everyone should be clamoring to hire.”

And they do that while making the same amount of money as their male counterparts. Mileage rates are typically blind to gender, after all. Male tractor-trailer drivers in the National Household Survey reported a median income of $45,681 in 2016, compared to women who made $36,392. But Uvanile-Hesch believes that difference would be influenced by women who might be more likely to lean toward regional or daily work.

The work continues in a bid to help recruit and retain more women, and increase their ranks beyond the stubbornly low share of 3.5%.

Today, Bison itself can count 3.8% of its drivers as women, up from 2.3% just over a year ago when it established a dedicated effort to attracting more female candidates.

“We have moved the needle,” Clark says. “We’ve made an indent.”